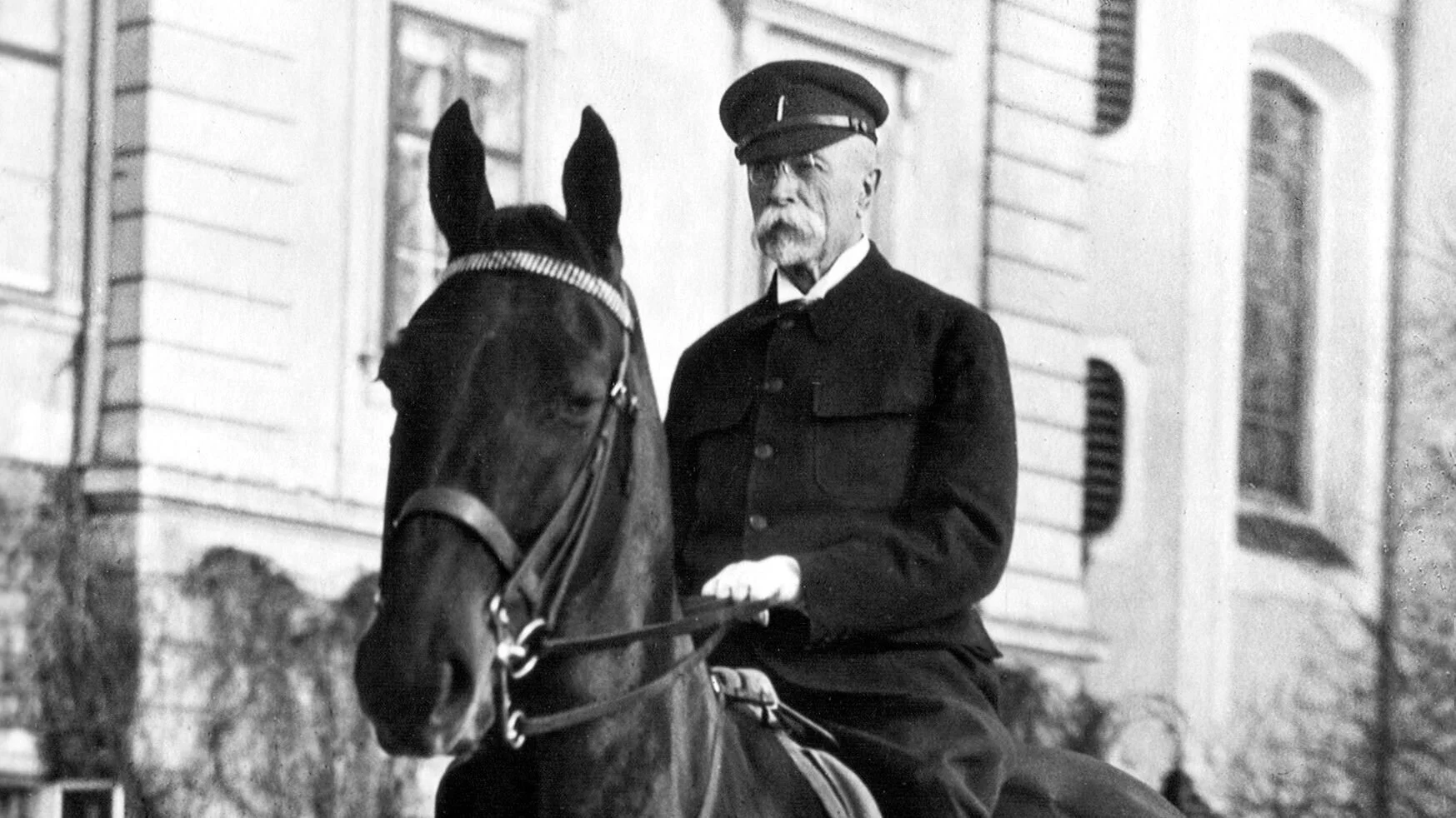

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

Father of a Nation

1850-1937

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk was a Czech politician and statesman who started the Czechoslovak independence movement and became the co-founder and first democratic president of the state of Czechoslovakia.

Born in 1850 in Moravia, Austro-Hungarian Empire, he received his Ph.D. from Vienna's University in 1876. Masaryk continued his education at Leipzig University, where he got to know his future wife, the American Charlotte Garrigue. He married her in the United States and took on her maiden name. In 1881, they settled in Prague, where he obtained a professorship at the city's University.

Masaryk joined the Young Czech party and served on the Reichsrat, an imperial council, from 1891-1893. The party had been born out of the 1848 Revolutions and the creation of Austria-Hungary with the Compromise of 1867. The Compromise provided a template for a new type of imperial federalism which could be used to give equal status to subjects while maintaining the power of the Habsburg Dynasty. The possibility of greater autonomy within the Empire brought on much uncertainty surrounding the future of the Czechs. This uncertainty would come to be known as the "Bohemian Question" and would shape Czech political theory and goals going into the 20th century.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Masaryk decided that the best answer to this question was to seek independence from Austria-Hungary. He went into exile and began campaigning abroad to establish Czechoslovakia's foundation. He would travel to many nations, including the United States, to win over politicians and journalists for the Czech cause. He also set up a spy network that reported Habsburg operations to the Allied forces. Together with other Czech and Slovak émigrés, he formed the Czechoslovak National Council and supported the Czechoslovak Legion - Czech and Slovak armed forces fighting for the Allies.

In his visit to the United States, Masaryk would go to Chicago, where 150,000 people from the Czech immigration hub welcomed him in the streets. Using his connections abroad, he was able to secure a meeting with President Woodrow Wilson. Though Wilson was not sympathetic to the weakening of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Masaryk and his associates were unrelenting. He toured the United States to gather support from Czech and Slovak communities, strengthened the Czechoslovak Legion in its fight against the Central Powers, and, together with other international émigré communities, put pressure on the Allies to support the cause. By the fall of 1918, the United States, followed by other Allies, recognized the National Council as a provisional government. Masaryk drafted the Czechoslovak declaration of independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which included freedom of religion, speech, the press, separation of church from the state, universal suffrage, and equal rights for women.

As the war neared its end, it became clear that the collapse of Austria-Hungary was imminent. On October 28, 1918, people could no longer contain their enthusiasm - they gathered in the streets of Prague and hoisted red and white Bohemian flags in the air as soldiers tore off imperial symbols and replaced them with Czechoslovak cockades. A group of Czech politicians took control of the city and proclaimed independence. Together with the Slovaks’ own Martin Declaration just two days later, this marked the creation of a free Czechoslovakia. By the end of the war, Masaryk was recognized by the Allies as the interim leader of the country and would go on to be elected as president three times. He would pass away in 1937 - the father of a nation.